|  | |||||

THE WRECK OF THE STEAMSHIP STELLA (BLISS) This disaster was a major factor in the introduction of safety regulations for shipping, and the eventual nationalisation of the railways. There is a memorial to Mary Rogers in Liverpool Cathedral - a stained glass window depicting the wreck (and there are others in London and Southampton). One small boy, Bening Arnold, (whose son now runs The Alderney Society Museum) survived because his mother had the foresight to tie his football by the laces to the collar of his shirt. The flooded lifeboat (in which his mother, brother and many others perished) was swept by the tide up and down The Swinge for nearly 24 hours before being taken in tow off the French coast. (His father's memoir appears below)* There were once three lighthouses on Les Casquets (as the above picture shows), arranged in a triangle so that mariners could judge their position by the orientation of the lights: St Peter, St Thomas and Donjon. (The Trinity House site is in error saying 'Dungeon." The name was Donjon - traditionally name of the highest turret in a medaeval castle). BLISS: vocal, half capo-ed guitar, NAPPER, mandolin and vocal

Maunday Thursday, 1899, It was South from Southampton we sailed Bound for Guernsey, the weather oh so fine No hint of a storm or a gale Full 19 knots, The Stella she could do As the London And South Western loved to boast But we slowed right down, when misty came the view And fog followed in like a ghost

Land Ho! Land Ho! St Peter, St Thomas and Donjon Land Ho! Land Ho! St Peter, St Thomas and Donjon

Now Captain Reeks, was a man of fine repute But the pressure could not be denied With the Great Western Railway, rivals on this route He must beat the other ships and the tide So, sure of his course, he ordered full ahead To the passengers mounting alarm For the glory of the Company, through the fog we sped Over seas so uneasily calm

I was up in the bow when, out of the white The Casquets rose up like a cliff With the helm hard a-starboard, the first contact was slight But we’d no chance of clearing the reef With a terrible rending, the hull was torn apart And every man on board knew the score With the White Ship, the Victory, a hundred on the chart The Casquets was taking one more

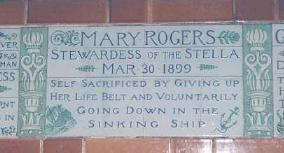

All calm and in order, six boats were got away With the half who’d escape being drowned As wives and husbands, grim goodbyes did say They handed the lifebelts around But Stewardess Rogers, she gave up her own To a passenger charged to her care Refusing a place lest the boat should overturn She went into the sea with a prayer

Now Captain Reeks, his very best did try But he knew that the price must be paid With his hand on the rail, and his face to the sky He went down with his ship to her grave One hundred died, that dreadful Easter Eve The day that the Stella was lost Victim of the system, leaving us to grieve And the shareholders counting the cost

This extract is from MEMOIRS OF BENING ARNOLD (Senior) 1824 -1930 (kept with the old three-volume 'family bible') with thanks to Peter Arnold MBE (his Grandson) Curator of Alderney Museum On the Thursday before Good Friday in the year 1899 my wife with our two boys Bening Mourant and Claude left home in Baker Street, W. to go to Guernsey by a special day boat from Southampton. On the doormat at parting as if she had a prescience of what was to happen she said to me I fear there will be a fog, and she gave me a more affectionate kiss than usual. There was an intermittent fog, and at times the boat was slowed down. In the afternoon the captain went below to dine. When he came on deck again the engineer telegraphed him we have run so many revolutions, and must be near the Casquets. "The Casquets are there" the Captain said pointing behind him over his left shoulder. A few minutes later the boat crashed upon the Casquets, and was a wreck. The engine room was full of water. There was cry for the "Boats!" and "Women and children first". One boat loaded was got off, but the steamboat sank before another boat could be loaded. All went down. Bening Mourant was a good swimmer, and when he came to the surface he looked about for his mother and brother, but not seeing them swam to an overturned lifeboat on which there were already 14 people. Two others got on after my son making 17 in all. In the night a big wave knocked the lifeboat over. Four of the company were unable to reach it. In the night several people died of exhaustion and were put overboard. The plug was out of the lifeboat, it was full of water, and they could not row properly. About 2.0 a.m. they drifted in sight of two red lights. An officious man, who ordered everybody about, shouted. "Look, you fellows, two lights and this reef of rocks close by, very dangerous, row away as hard as you can” My son said "Those two lights are the lights of Alderney. If we row to them we shall get to land and be safe." "What can a boy like you know about it?" "I spend my Midsummer holiday in Alderney, and I know those two lights well" my son replied "Oh nonsense, two lights to a harbour! They mean special danger. Row, row you fellows" And they did row, and managed to get to the nose of the breakwater, where the sea ran at 7 miles an hour. The boat got into the sea race, and was carried down towards the French coast. When day came on. they hoisted an oar with a white handkerchief tied on it. After drifting some hours in the Race of Alderney, they were seen by a signalman on the French coast, who telegraphed to Cherbourg that there was a shipwreck, and a boat adrift in the Channel, or Race of Alderney. A steamboat was sent out from Cherbourg to look for them. Fortunately they were found. When I came home from church on Good Friday I found a telegram from Guernsey awaiting me. It was to tell me that there had been an accident, and I must come to Guernsey at once. I left Southampton that night. When I got to Guernsey I learnt that my dear wife and Claude were drowned, but Bening was safe in Cherbourg. There was a boat going there in half an hour. I went by it. Found my boy. He could not speak reasonably. Indeed he had been delirious, and wanted to get out of the rowing boat to go and find his mother and brother. Finding it useless to press conversation I got him into fresh clean clothes and we came together back to Guernsey. When I got there I learned that Claude's body had been found just outside Alderney harbour. I went up to Alderney next morning. Could not go before. Bought a plot of land in the churchyard, got a coffin made, and buried child the same day. Next day I returned to Guernsey and then home, leaving Bening behind with children, thinking he would be less unhappy with them than with me. | ||

| ||